Teaching the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans: Responsive Strategies for Educators & Clinicians

At first glance, the 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGAs) may appear somewhat familiar. They reinforce longstanding themes that have been taught for years: Focus on overall dietary patterns, prioritize nutrient-dense foods, and limit added sugars, sodium and saturated fat.1 However, the new guidelines have both strengths and ambiguities that should be interpreted thoughtfully.

The Core Message: ‘Eat Real Food’

The new guidelines seek to simplify public nutrition guidance while signaling a renewed emphasis on whole, minimally processed foods and taking a strong stance against excess added sugars and highly processed foods.1

In their introductory message to the guidelines, the secretaries of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. Department of Agriculture state that “The message is simple: Eat real food.”

While the slogan seems easy to grasp, translating it into meaningful learning experiences requires careful consideration. What qualifies as “real food” in culturally diverse diets? How do we balance convenience, affordability, and access? These are the practical questions educators and clinicians will need to address when translating this message into real-world guidance.2

Key Recommendations at a Glance

The 2025–2030 DGAs outline several broad recommendations intended to support lifelong health:1

- Eat the right amount for you.

- Prioritize protein foods at every meal.

- Consume dairy.

- Eat vegetables and fruits throughout the day.

- Incorporate healthy fats.

- Focus on whole grains.

- Limit highly processed foods, added sugars, and refined carbohydrates.

- Limit alcoholic beverages.

Many of these points echo earlier guidelines and reflect strong scientific consensus around dietary patterns that reduce chronic disease risk.3,4

Considerations for Special Populations

The DGAs continue to provide tailored guidance across the lifespan, for people with chronic diseases, and for people who are vegetarian or vegan. This approach, covering infancy through older adulthood, supports the idea that nutrition needs evolve throughout the lifespan.

Controversies Surrounding the 2025-2030 Guidelines

Alongside these recommendations, several areas warrant careful examination. As educators responsible for preparing the next generation of nutrition professionals, it's essential to approach these guidelines critically and help students understand both their strengths and limitations.

The following controversies highlight areas where the guidelines may create confusion or conflict with established evidence.

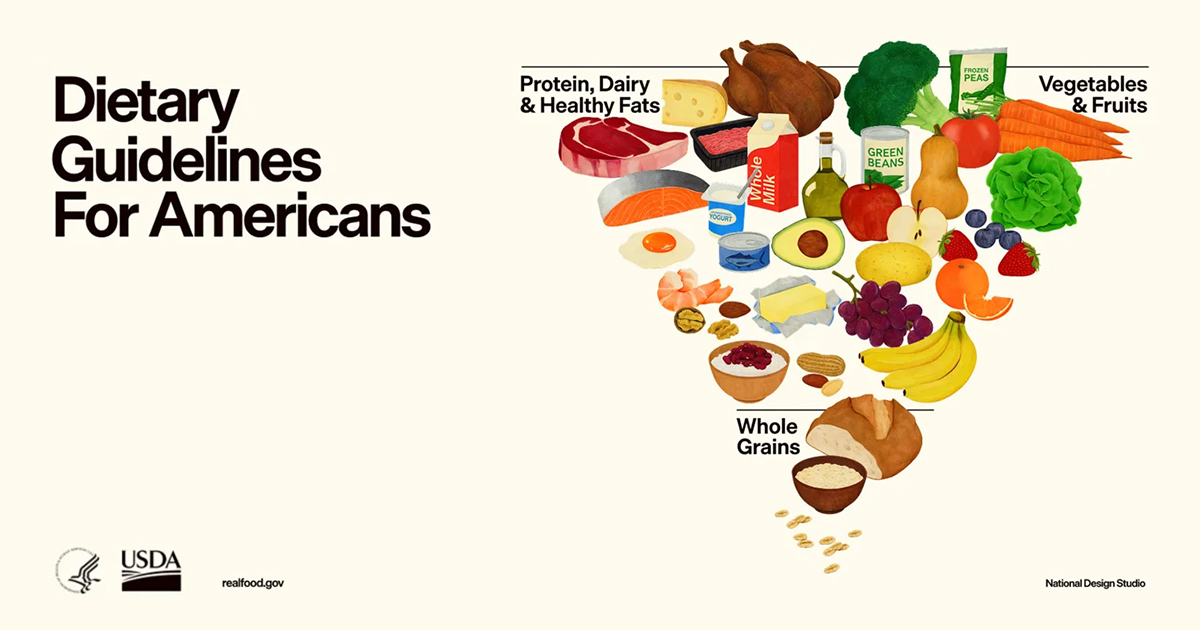

1. Visual changes and educational implications

Without clear explanation and educational framing, the inverted pyramid graphic risks oversimplifying the complexity of diet, potentially misleading users about the hierarchy of food importance.

2. Protein: More is not always better

The guidelines suggest higher thresholds of protein intake and recommend including protein at every meal. While protein plays a critical role in satiety, muscle maintenance, and metabolic health, this recommendation raises important concerns.

First, the suggested increase represents a 50% to 100% jump above the current Dietary Reference Intakes, which most Americans already meet or exceed.5 Furthermore, while higher protein intake may benefit people engaged in regular strength or resistance training, there is limited evidence to support broad population-level benefits at these intake levels.

It is important to also note that without appropriate physical activity, excess protein can be converted to fat by the liver, potentially increasing visceral adiposity and long-term diabetes risk.6 These suggested protein intake guidelines lack strong scientific justification and may draw attention away from overall dietary quality.

3. Saturated fat: Mixed messages

Perhaps the most debated element of the 2025–2030 DGAs so far is the continued cap on saturated fat intake (no more than 10% of calories) alongside what appears to be encouragement of foods rich in saturated fat. The depiction includes full-fat dairy, butter, beef tallow, and higher-fat meats — creating a messaging contradiction.

Decades of evidence link higher saturated fat intake with increased low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and cardiovascular disease risk.7 The emphasis on higher protein intake combined with renewed attention to full-fat dairy and animal fats does not align with mainstream nutrition science consensus. For clinicians and educators, this ambiguity may make it harder to translate the guidelines into practical, coherent advice.

4. Are the guidelines too broad?

Another ongoing critique is that the DGAs may be too general to meaningfully guide individual choices. The slogan “Eat real food” resonates emotionally, but it does not replace the need for specific, actionable strategies. This is especially true for populations facing food insecurity, chronic disease, or cultural dietary constraints.8

Applying the Guidelines Responsibly

For nutrition professionals, the 2025–2030 DGAs should be treated as a framework — not a rigid prescription. Educators should:

- Emphasize evidence-based principles over slogans.

- Clarify where guidance is evolving versus where scientific consensus remains strong.

- Tailor recommendations to cultural traditions, preferences, and food access realities.

- Promote practical strategies such as water intake, meal planning, and budget-conscious food choices.

- Use visuals as support tools, not primary teaching devices.

Final Thoughts on the New DGAs

The 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans reinforce core nutrition principles like prioritizing nutrient-dense whole foods, limiting added sugars and highly processed foods, and focusing on overall dietary patterns. Mixed messages around protein and saturated fat highlight the ongoing challenge of translating emerging research findings into legislative policy and general health messaging.

For educators, clinicians, and food service professionals, the key is not just adopting the guidelines but applying them thoughtfully in diverse populations. Emphasizing evidence-based practice, acknowledging uncertainties, and treating the guidelines as a flexible framework can help ensure they remain a helpful tool rather than a source of confusion.

References

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services & U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2026). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2025–2030. U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://cdn.realfood.gov/DGA.pdf

- Kumanyika, S. K. (2019). A framework for increasing equity impact in obesity prevention. American Journal of Public Health, 109(10), 1350–1357. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2019.305221

- Mozaffarian, D. The 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines. (2025). Time for Real Progress. JAMA, 333(13), 1111-1112. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.0410

- Willett, W., Rockström, Loken, B., Springmann, M., et al. (2019). Food in the Anthropocene: The EAT–Lancet Commission. The Lancet, 393(10170), 447–492.

- Institute of Medicine. (2006). Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements. National Academies Press.

- Westerterp-Plantenga, M.S., Lemmens, S., & Westerterp, K. (2012). Dietary protein and energy balance. Physiology & Behavior, 106(3), 416–421. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00443

- Hooper, L., Martin, N., Jimoh, O. (2020). Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Aug 21, 8(8). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32827219/

- Drewnowski, A., & Eichelsdoerfer, P. (2010). Can low-income Americans afford a healthy diet? Nutrition Today, 45(6), 246–249. doi: 10.1097/NT.0b013e3181c29f79

About the Authors:

Kimberley McMahon, MDA, RD, LD

Kimberley McMahon is a registered and licensed dietitian in Nevada who currently teaches nutrition and dietetics at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. McMahan is a coauthor of Discovering Nutrition, Nutrition, Nutrition Across Life Stages, Nutrition Essentials and Eat Right! Healthy Eating in College and Beyond.

McMahon was previously an instructor at Utah State University, Northern Kentucky University, and Logan University. Her interests and experience are in the areas of wellness, weight management, sports nutrition, and eating disorders. She received her undergraduate degree from Montana State University and master’s degree from Utah State University.

Melissa Bernstein, PhD, RDN, LD, FAND, DipACLM, FNAP

Melissa Bernstein is a registered dietitian nutritionist and licensed dietitian who is Chair of the Department of Nutrition at Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. She also serves as an associate professor at Rosalind Franklin University and at Chicago Medical School.

Dr. Bernstein is a Fellow of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and a Diplomat of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine. She is the coauthor of the Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Food and Nutrition for Older Adults: Promoting Health and Wellness. In addition to co-authoring Nutrition, Discovering Nutrition, Nutrition Essentials, Nutrition Across Life Stages, Nutrition for the Older Adult, and Nutrition Assessment: Clinical and Research Applications, she has contributed, authored, and reviewed textbook chapters and peer-reviewed journal publications and participates on numerous advisory and review boards.

Dr. Bernstein received her doctoral degree from the Gerald J. and Dorothy R. Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy at Tufts University in Boston. Her interests include nutrition for a healthy lifestyle, physical activity, and holistic wellness.