Teaching Public Health in the Climate Crisis

Young people all over the world are worried about climate change. Last week, the media reported on a forthcoming study that surveyed 10,000 youth ages 16-25 in 10 countries and found that most of them have a wide range of negative emotions regarding climate change, including feeling anxious, afraid, sad, angry, helpless, and powerless. Most survey respondents reported feeling “extremely” or “very” worried, especially in countries already hard-hit by climate change impacts, including the Philippines and India. Three-quarters believe the “future is frightening,” and more than half said that “things I value [are being] destroyed.”

Young people have reason to be worried. A new study in the journal Science estimates that people born in 2020 will experience 2-7 times as many climate disasters as people born in 1960. Because this is a “severe threat to the safety of young generations,” the authors “call for drastic emission reductions to safeguard their future.”

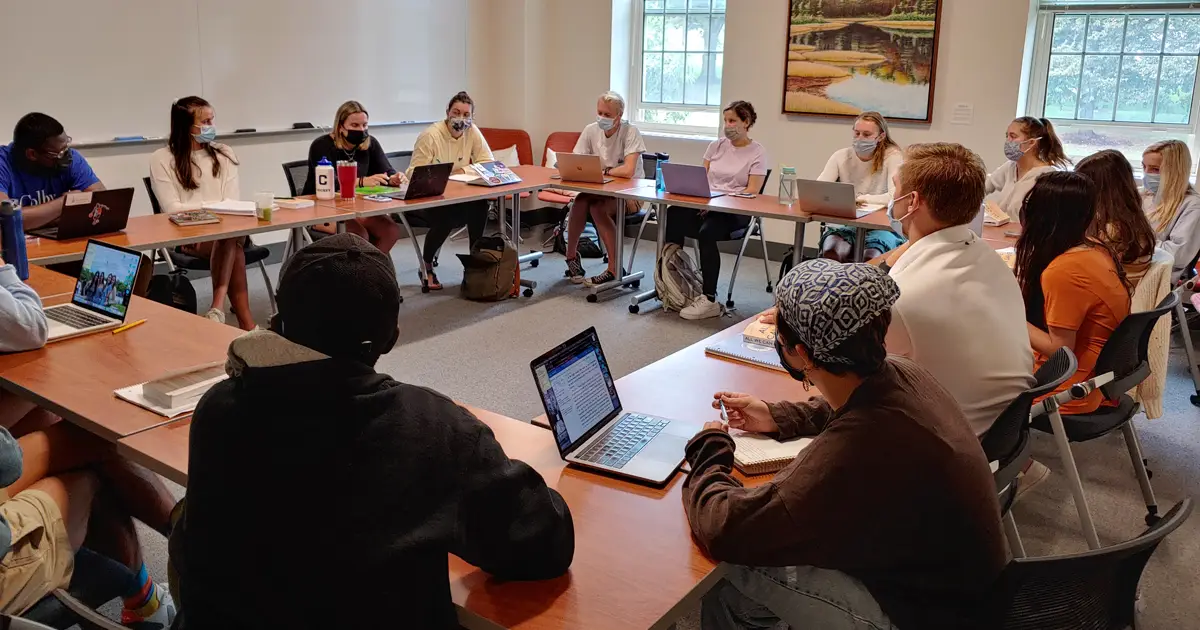

I can attest to these prevalent feelings of anxiety among young adults, having taught undergraduates in the Environmental Studies Program at Colby College for 17 years. My students have expressed a similar range of emotions regarding what they think and feel about climate change. They are tired, worried, angry, terrified, frustrated, discouraged, and panicked. They see that they have a lot to lose, that serious climate impacts are already occurring, and that despite understanding the problem for decades, dangerous inaction persists on the part of decision-makers.

Some of my students have first-hand experiences of these climate change impacts. Some live in coastal areas imminently threatened with inundation, even complete disappearance, because of sea-level rise. Others live in cities that have been damaged by scorching wildfires, even having to evacuate their homes. One student working out west this summer witnessed the Great Salt Lake dry up before his very eyes. These students are angry, sad, and scared for what they are losing in their own lives, and they also know that some people are being impacted much worse, which they believe obliges us to act in a rapid and determined manner. They also see that there’s no separating health and environment.

Climate change magnifies human health problems in so many ways, causing significant excess illness, suffering, and mortality. From exposure to heat waves, extreme floods, and wildfire smoke to experiences of drought, water scarcity, crop failures, and migration pressures, people are facing physical and mental health threats that grow each year. The World Health Organization projects that between 2030 and 2050, an additional 250,000 people worldwide will die each year from just four climate change-related causes: childhood undernutrition, malaria, diarrheal diseases, and heat exposure in the elderly.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted our serious public health challenges and health inequities, and at the same time, we are seeing climate change devastate people’s lives in so many ways. These existential crises interact and must be addressed in an intersecting light. We need to tackle climate change to prevent its devastating effects on health and strengthen our public health systems to better protect people and prepare for and respond to our changing climate.

My students will graduate soon and enter a world unprepared to deal with the human health impacts of climate change. This is a challenge that older generations didn’t have to think about when they entered the work world. Teaching students how climate change impacts human lives prepares them to understand what will be gained by rapidly reducing greenhouse gas emissions driving climate change and give them the tools to create compelling, responsive, and equitable climate actions and adaptations that improve well-being.

My students feel hopeful that their generation will make a difference. One student reported, “I think the most impactful thing is watching my peers here at Colby studying environmental science and policy be trained in and passionate about protecting the world around us. We have no time to lose, and our students, well-trained in public health and climate change, will lead the way. In colleges across the country and world, there are students like those at Colby that want to make it their life’s work to elicit change in the trajectory of climate change, and that is what gives me hope for the future.”

About the Author

Gail Carlson teaches environmental public health at Colby College, where she directs the Buck Lab for Climate and Environment. She is the author of the forthcoming textbook, Human Health and the Climate Crisis (January 2022, Jones & Bartlett Learning), designed for courses on climate change and public health for undergraduates, graduate students, and students in the health professions.