Teaching Evidence-Based Motivational Interviewing Techniques

Public responses to social distancing and face mask requirements as preventive measures against the novel coronavirus, SARS-COV-2 (the organism that causes COVID-19), hearken back to similar reactions to laws related to raising the legal age to purchase tobacco products, requirements to wear seat belts, bans on indoor smoking, and laws regarding motorcycle helmets. The reasons for resistance given by our patients when discussing preventive measures often center on the issue of autonomy. An evidence-based motivational interview (EBMI) offers helpful strategies to educate patients in a manner that respects their self-determination while promoting healthy behaviors.

Motivational interviewing is a well-established, patient-centered technique for stimulating patients to change behaviors such as smoking, nutritional choices, exercise, substance abuse, child car seat usage, and more.1 Even for patients with low readiness to change, EBMI can serve as a prelude to later reconsideration. An EBMI approach includes the following elements:

- Best-available research evidence – for health professional reference

- Evidence-based patient education materials

- The five principles of motivational interviewing2

- Using reflective listening to express empathy

- Identifying inconsistency between the patient’s behavior and their goals or values

- Avoidance of direct confrontation and argument

- Rolling with resistance

- Supporting self-efficacy

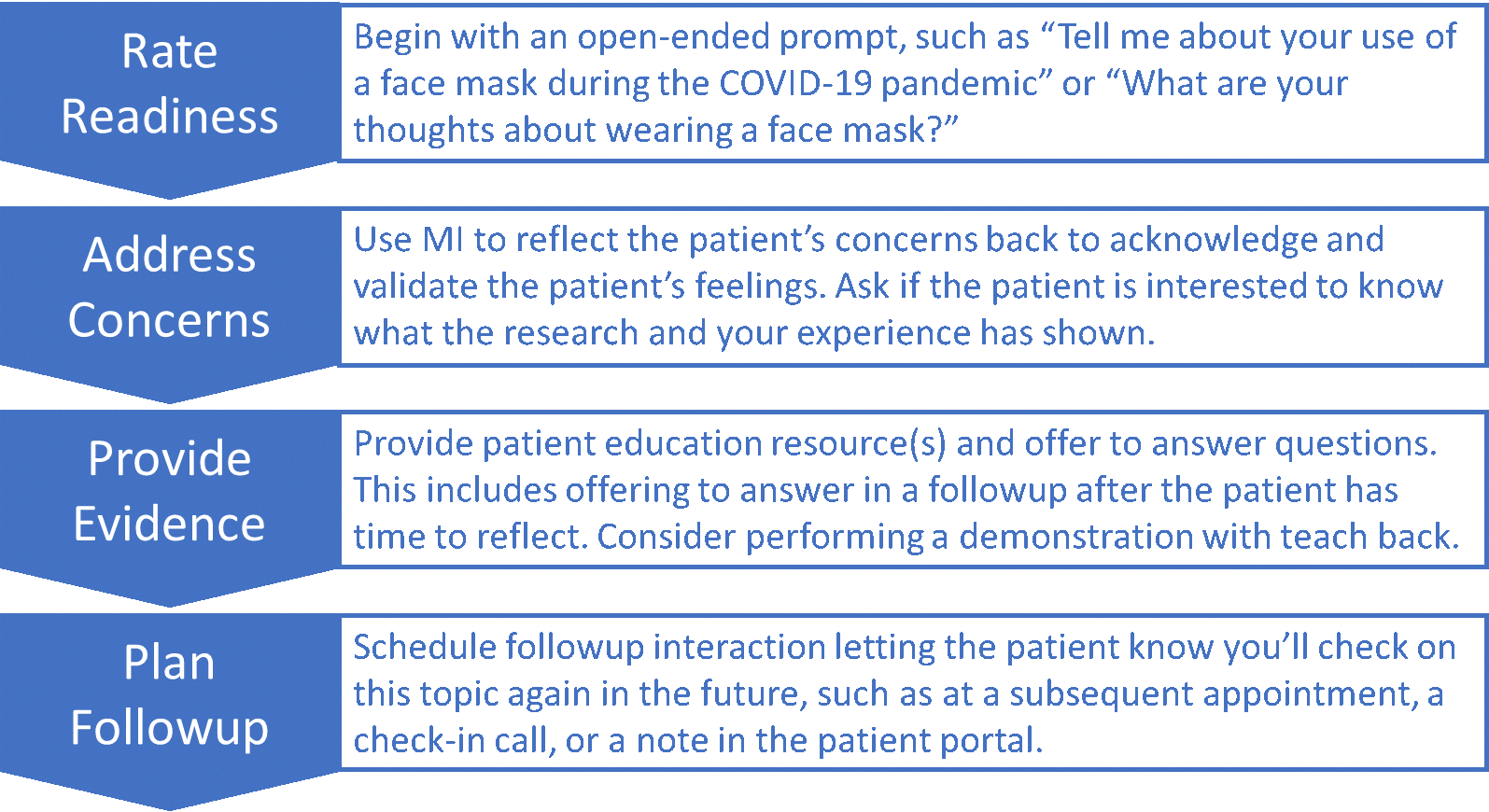

Figure 1: Stages of an EBMI Encounter

An EBMI encounter begins with an open-ended prompt as displayed in Figure 1. The response from the patient will provide insights into the individual’s concerns and readiness to consider developing the habits of maintaining social distance and wearing a face mask, as appropriate to their situation. A readiness question could follow, such as “On a scale of 1 to 10, how ready are you to start wearing a face mask, with one being ‘not at all,’ and ten being ‘I’m ready today?’” Additionally, during the conversation, the provider explores the patient’s values related to preventing illness.

Consider a patient who agrees that when it comes to other diseases, they would not take the risk of infecting a loved one, but the patient also believes that COVID-19 is not more hazardous than seasonal influenza. A patient-centered response in this situation might be:

I think it’s great how much you care about protecting your loved ones. You don’t believe COVID-19 is a serious health risk for them. If you had the flu, what steps would you take keep from infecting them? What worries you about wearing a face mask?

The responses to the last question could open opportunities to mention the research and provide patient education resources.

Based on what you’ve told me, you might not be interested to know what the research has shown. I have some information here that describes what we know about this illness and how it spreads between people who are in close contact with one another. Would you be willing to look this over? We can talk about this when I see you for your followup if you’d like.

It is important to end the encounter with a plan for the next steps to let the patient know you will check with them again on this topic in the future. Patients who express low levels of readiness during an initial conversation might return with increased readiness at a later time.

Health professionals are allies to patients through our understanding that changing behaviors is a process that can require many attempts and involve setbacks. Patients often go through phases according to the transtheoretical model.1 As such, it is essential for us to be persistent and patient through the stages from pre-contemplation to contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance. And, perhaps most importantly, we must respect the patient’s self-determination when they choose not to follow our recommendations while maintaining our commitment to encouraging healthy choices.

About the Author

References:

- Howlett B, Rogo E, Gabiola-Shelton T. Evidence-based practice for health professionals: An interprofessional approach. Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2020: Burlington, MA.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. Guilford Press; 1991: New York.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Recommendation for cloth face covers. Updated April 3, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover.html#:~:text=In%20light%20of%20this%20new,community%2Dbased%20transmission.

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, Solo K, Yaacoub S, Schünemann HJ, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2020 June 27; 395(10242). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9