Underserved populations continue to be at disproportionate risk for adverse health outcomes. We have known for quite some time that increasing the diversity of the health care workforce is an important solution to this problem. Students from underrepresented groups continue to experience a lack of access and barriers to persistence in their education pathways, which results in limited representation in the health professions and ultimately contributes to the health outcome disparities experienced by African American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latino, Pacific Island, and other groups.1Jackson and Gracia explained, “Racial/ethnic diversity in the health-care workforce [sic] has been well correlated with the delivery of quality care to minority populations.”

As such, the health science education system needs additional strategies that support the success of students from these groups. Mentoring is widely used as an educational strategy in health science education. It normally occurs in a traditional, hierarchical form, which can inhibit access and persistence for underrepresented groups. It is critical for health science education to intentionally shift mentoring relationships from traditional forms to an egalitarian paradigm to reduce negative impacts from the inherent power differential that can contribute to limiting access to health professions for racial or ethnic minority students.

Mentoring is an essential activity in health science education, involving formal (such as faculty members serving as assigned advisors) and informal relationships (such as students seeking advising at key moments in their education). Formal mentoring can include an additional aspect of graded and ungraded interactions. A graded form of mentoring occurs with clinical rotations, and sometimes also happens in the context of didactic instruction. Ungraded mentoring is typically represented by the advisor/advisee relationship.

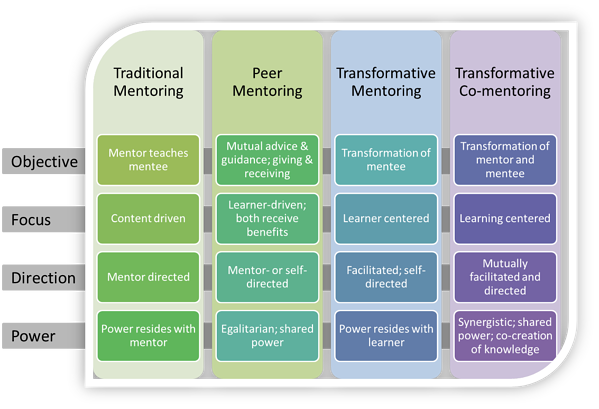

Both formal and informal approaches in traditional mentoring relationships include power differentials that can inhibit the development of the student, and even miss development opportunities for the faculty member. In traditional mentoring, the growth and learning of the student is the only goal, while the faculty member is expected to participate strictly as an expert. While eliminating the power difference is not possible (or even advisable), reducing the power disparity in mentoring relationships can alter the experience to open opportunities for transformative learning for both parties. Mentoring can be thought of as representing a spectrum of approaches, as represented in Figure 1, each with its objective, focus, direction, and power. Each form of mentoring has its place and appropriate uses.

Figure 1: Spectrum of Mentoring Approaches

Mentoring experiences become transformational for both participants when they approach the relationship from a perspective of openness to learning from one another, humility, egalitarianism, and commitment to resolving barriers. This type of mentoring relationship can lead to positive change and growth for all involved. Mentoring that possesses these characteristics is referred to as Transformative Co-mentoring (TCM).2 Note the distinction in Figure 1 with Transformative Mentoring in terms of the center/focus of the relationship. Transformative mentoring is focused on the learner, while transformative co-mentoring is focused on learning because both parties learn.

The first appearance of TCM in scholarly literature was in 20112 in a conference presentation based on a case study involving two Latinas. The authors explained a transformational experience in which the distinctions between mentor and mentee were blurred. According to Flores-Duenas and Anaya, a TCM relationship enables the participants to address micro-aggressions experienced by the student and support success through the educational pathway. In 2013 the concept of TCM was expanded to a mentoring theory by Austin and Howlett.3 TCM was further refined as the theory began to be formally applied in a TCM health science education pathway program for Hispanic/Latino and Native American youth.4,5 Applications of TCM have led to remarkable experiences for students and faculty alike in these types of programs, while also achieving the goal of enabling students from underrepresented groups to both persist and succeed in health and science education.

About the Author

Bernadette Howlett, Ph.D. is an author, consultant, and educator who teaches evidence-based practice as an adjunct faculty member. She has been the Director of a research institute and also a Chief Research Officer of a medical school. She was an associate professor and research coordinator for a physician assistant (PA) studies program. She is currently an affiliate faculty member with the Kasiska Division of Health Sciences at Idaho State University contracted to design and teach courses in evidence-based practice as well as interprofessional practice.

Notes:

- Jackson C.S., Gracia J.N. (Jan-Feb. 2014). Addressing health and health-care disparities: The role of a diverse workforce and the social determinants of health. Public Health Reports. 129(Suppl 2): 57-61. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3863703/

- Flores-Duenas, L., Anaya, M. (Oct. 2011). Transformational Co-Mentoring of two Latinas: Social and ethnic identity as a form of empowerment.

- Austin, J., Howlett, B. (Oct. 2013). Humility in mentoring: A model for fostering co-creation of knowledge. The Mentoring Institute Sixth Annual Mentoring Conference in Albuquerque, NM. Oct. 29 – Nov. 1, 2013. Proceedings available at https://mentor.unm.edu/content/conference-programs/conference-program-2013.pdf

- Ramos-Diaz, M.I, Strom, H.M., Howlett, B., Renker, A., Janis, M. (Oct. 2015). Roots to Wings: Using mentoring to form a health science degree pathway for Native Americans. 8th Annual Mentoring Conference. Albuquerque, NM.

- Ramos-Diaz M.I., Brings Him Back-Janis, M., Strom, H.M., Howlett, B., Renker, A.M., Washines (Yellowash), D.E. (2020) Roots to Wings Transformative co-mentoring program to foster cross-cultural understanding and pathways into the medical profession for Native and Mexican American students. In B. Irby, et al. The Wiley International Handbook of Mentoring. Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ.