In the Beginning of Time

I must begin with a picture that represents the “beginning of time” for my journey in global health. Here is a picture a Filipino photographer labelled as “Richard Skolnik’s triumphant arrival in the Philippines”. I had never left home before that and never been out of Illinois, Indiana, or Ohio. In 1966, I was selected to be an AFS summer exchange student to the Philippines, where I got the greatest exchange student family in history. My high school classmates raised money to pay for my trip. To all who were involved I remain very grateful, since this started an interest in and commitment to international development, from which I have never veered. In many ways, that trip got me where I am today.

Where I Am Coming from, Intellectually

Based on my almost 50 years of work in international development and health on about 50 countries, I am often asked to comment on the U.S. health system from a global perspective. I am NOT AT ALL an authority on the U.S. health system. I have never worked on health in my own country. There are many who know a million times more than I do about the United States. However, what I have had is the wonderful opportunity to work on health in many other countries, to write about what I have learned, and to consider its meaning for my own country.

I also need to remind you at the beginning that I believe that:

- health is a human right;

- the starting point for our discussion must be how to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) as fast as possible, at least cost, in the fairest possible way

- how money is spent on health is more important than how much is spent

- decisions about spending for health should be made in ethical and fair ways

- that gaps between our health status and that in other high-income countries are unacceptable

Thus, with profound humility, here are my thoughts from a comparative perspective on:

- The US health system,

- Key US health status indicators and health disparities

- What global lessons suggest might be done to address these issues

- The constraints to change in the US

- How progress might be made, even in the face of such constraints

The Good News

Let me begin by acknowledging that there are some things the U.S. has done well in health over the past several decades. These include, among others:

- Reducing tobacco consumption

- Auto safety

- Environmental and occupational health

- Reduction in cancer death rates

- Approach to disability

- Until recently, seeking to get more people insured

- Technological innovation for health

Yet, in a number of areas related to both health status and its health system, the U.S. compares poorly with other high-income countries and even a range of low- and middle-income countries.

The Health System

If the goal is Universal Health Coverage (UHC), then how do we stand compared to other countries in achieving this at least cost and in fair ways?

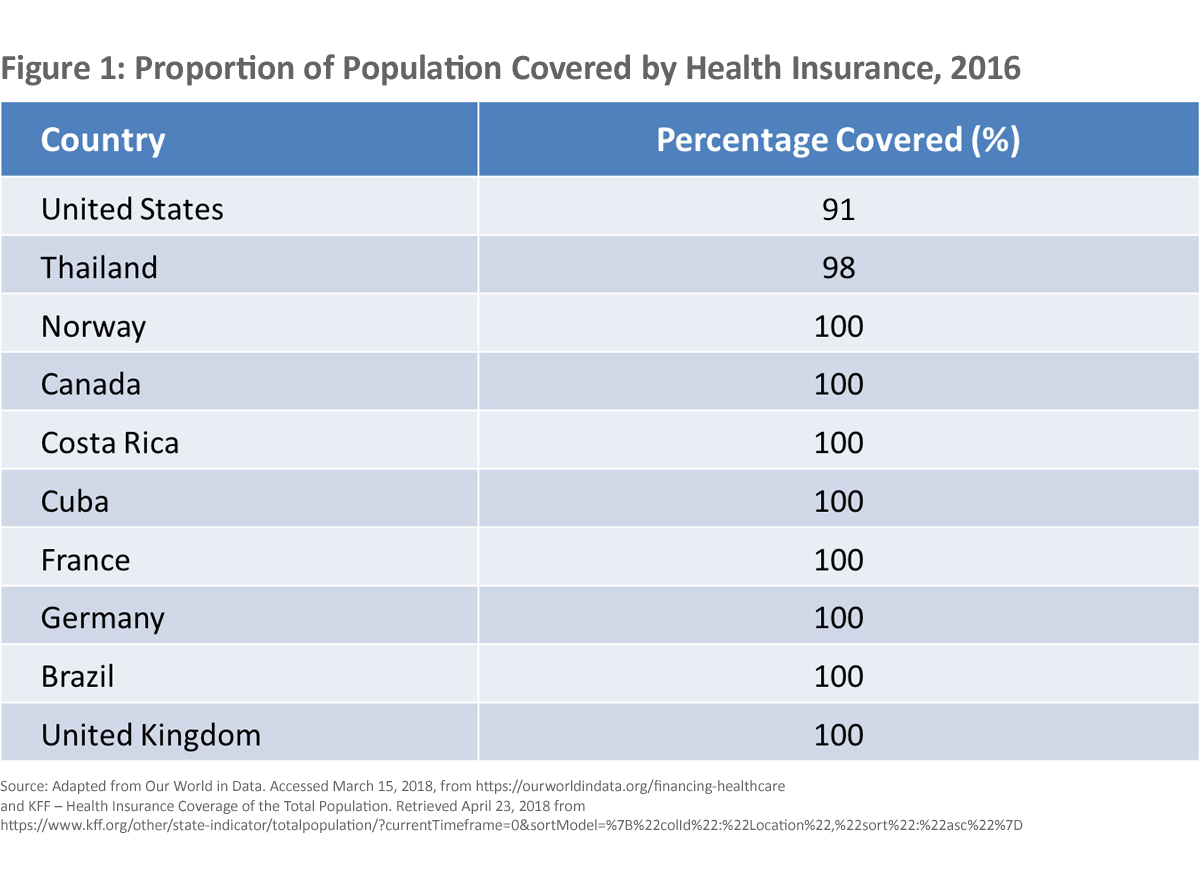

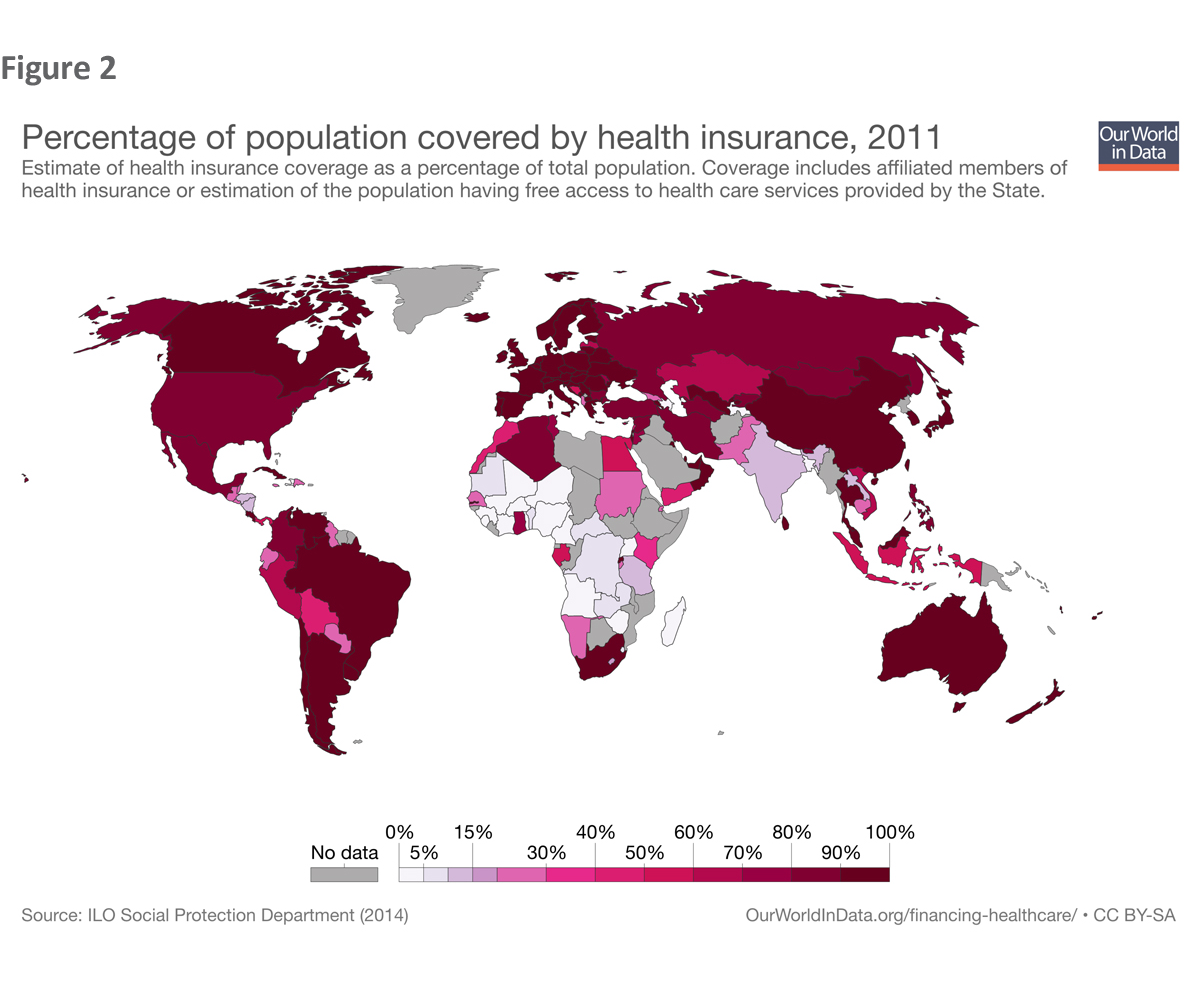

Figures 1 and 2 show how far we are from Universal Health Coverage. Every other high-income country and many other countries have achieved Universal Health Coverage. However, we are still quite far from it, with the latest data showing about 9% of the population being uninsured. The U.S. has a fragmented system that does not work for everyone and continually leaves people out.

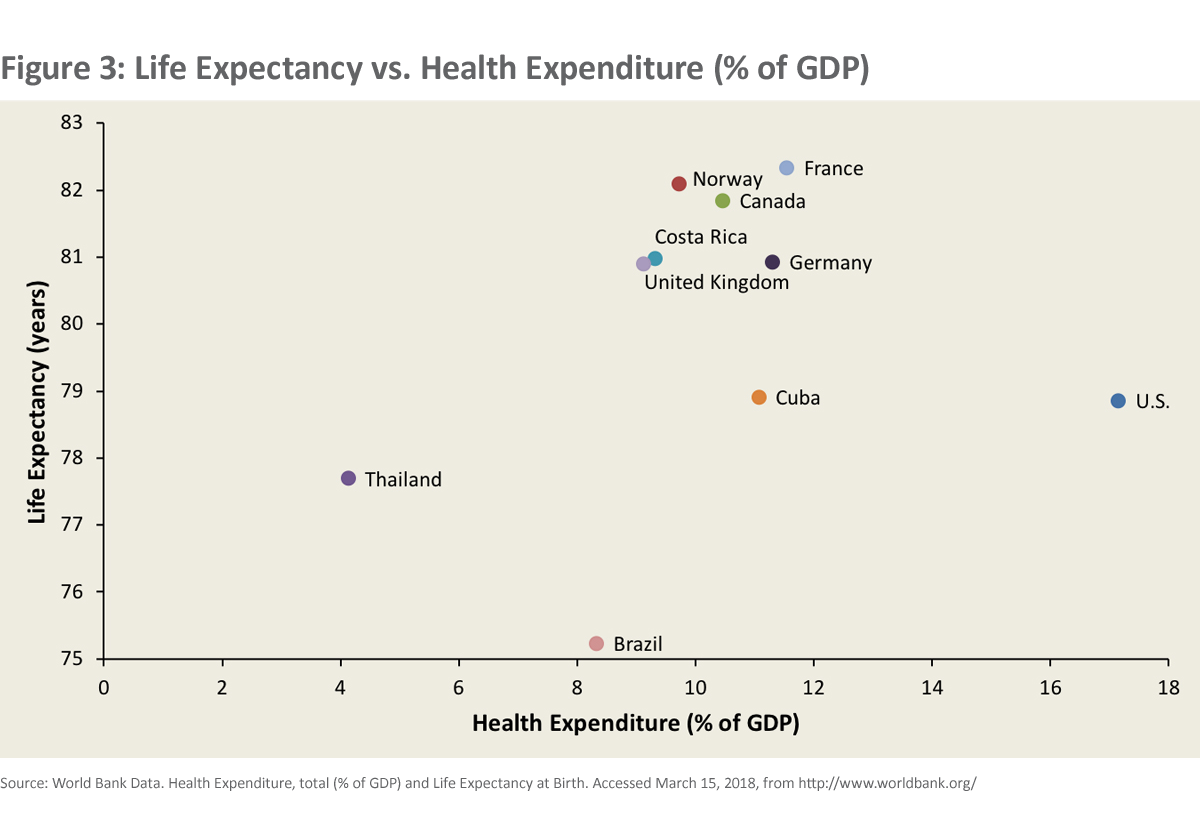

These failures are compounded when we consider that a country’s goal is to achieve UHC at least cost and in fair ways. As you can see in Figure 3, we spend at least 50% more on health as a share of GDP than any other high-income country. Yet, we don’t achieve greater life expectancy by doing so.

These failures are compounded when we consider that a country’s goal is to achieve UHC at least cost and in fair ways. As you can see in Figure 3, we spend at least 50% more on health as a share of GDP than any other high-income country. Yet, we don’t achieve greater life expectancy by doing so.

There are many markers of health system performance. However, I want to show just one.

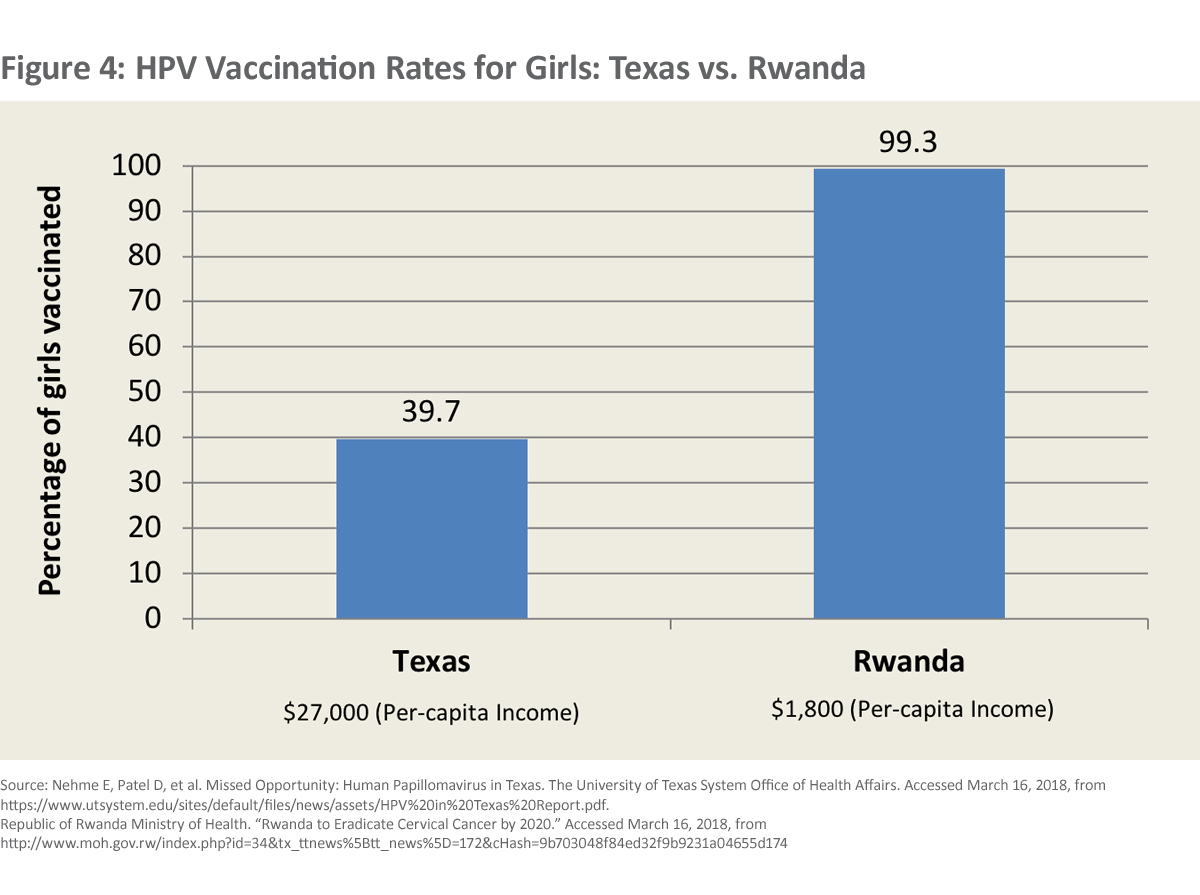

Figure 4 shows the HPV vaccination rate in Texas with a per capita income of $27,000, compared to that in Rwanda, with a per capita income of $1,800. Although Texas has a per capita income that is 15 times greater, Rwanda has an HPV immunization rate that is universal and 2.5 times that of Texas. Why are so many Texans failing to immunize their daughters against cancer? I must note, however, that vaccine skepticism in Europe is now so high that France’s HPV vaccination rate is only 19%.

Health Status Compared

Many factors influence health. We are also a large, complicated, and diverse country that calls itself a federal democracy. Nonetheless, let’s start our global view of the U.S. by examining how we compare with a number of comparator countries in the middle- and high-income world on selected indicators of health status.

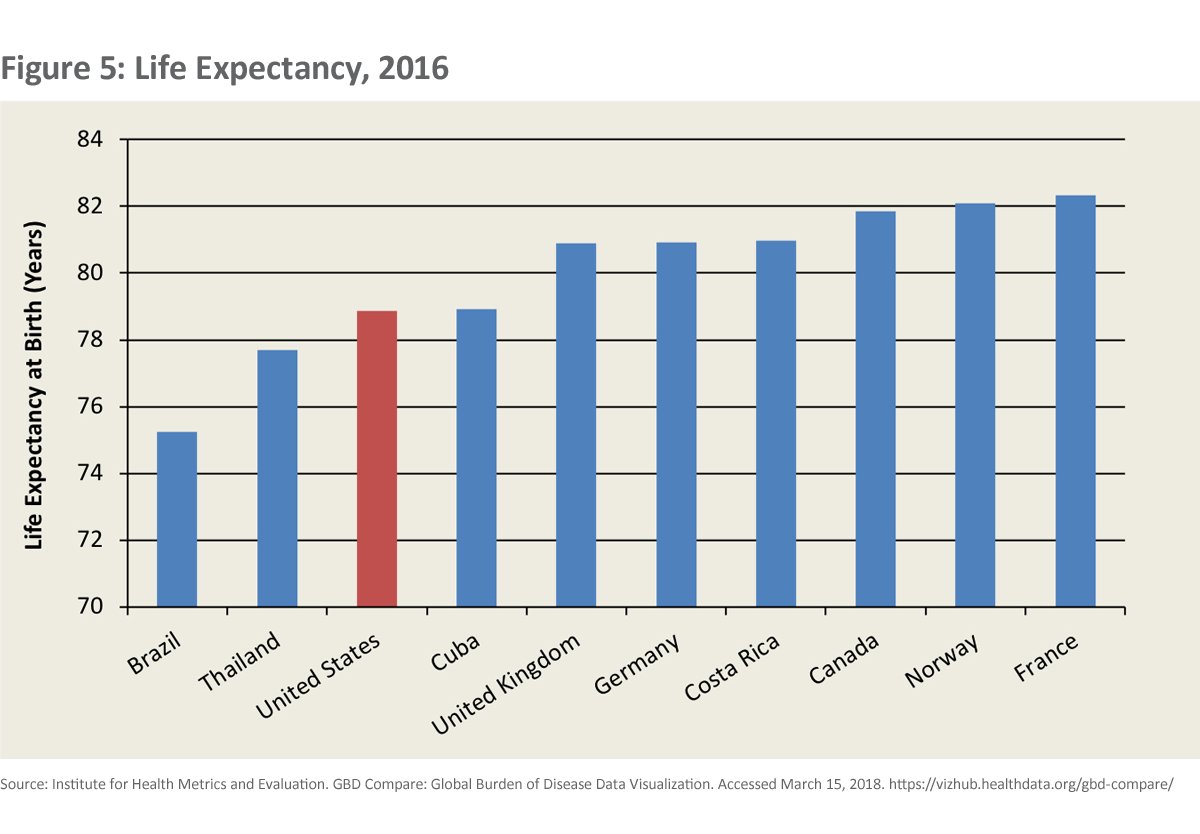

When we look again at life expectancy (Figure 5), we see that the U.S. lags behind each of the high-income countries noted. We can also see, that despite our relatively higher per capita income, that some middle-income countries have a higher life expectancy than we have.

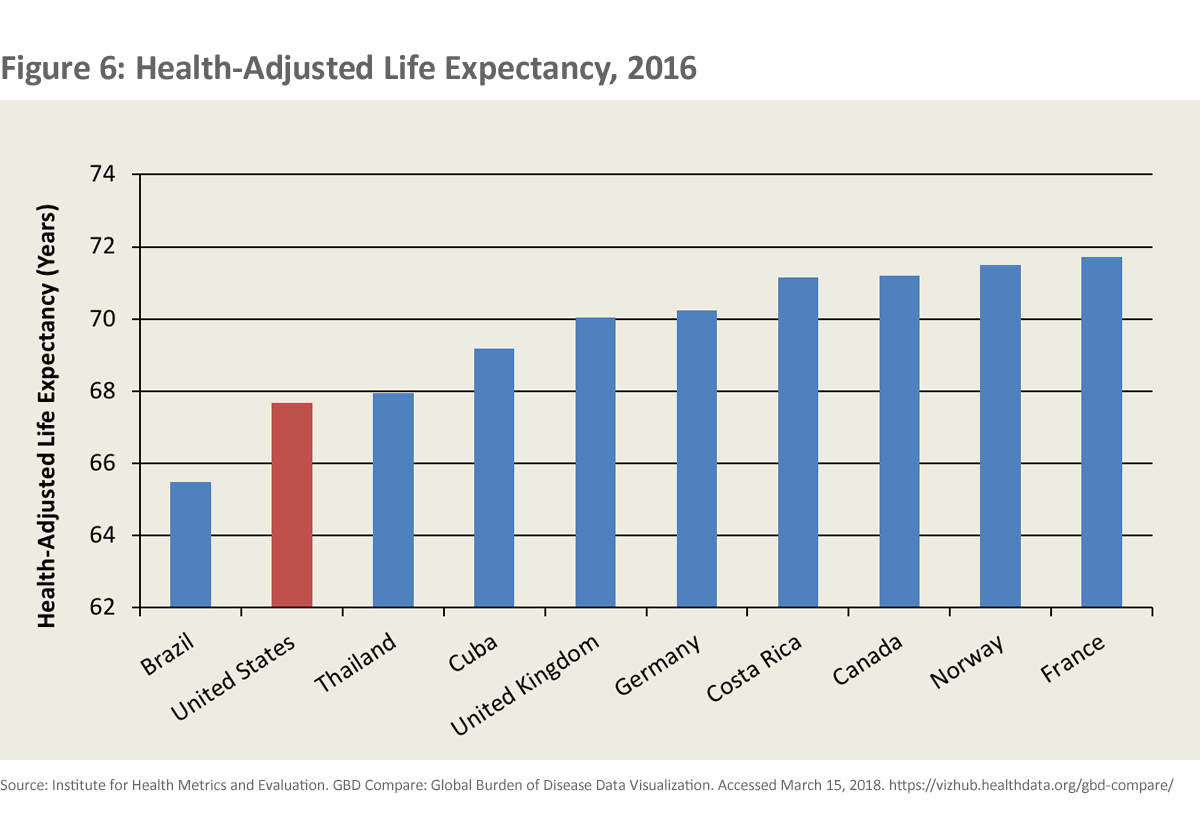

When we look at health adjusted life expectancy (HALE) (Figure 6), we see that health adjusted life expectancy in the U.S. dramatically lags behind almost all of our comparators. This says that, even if we live almost as long as people in many other countries, we live a more important part of those years in ill health or in disability than people do in the comparator countries.

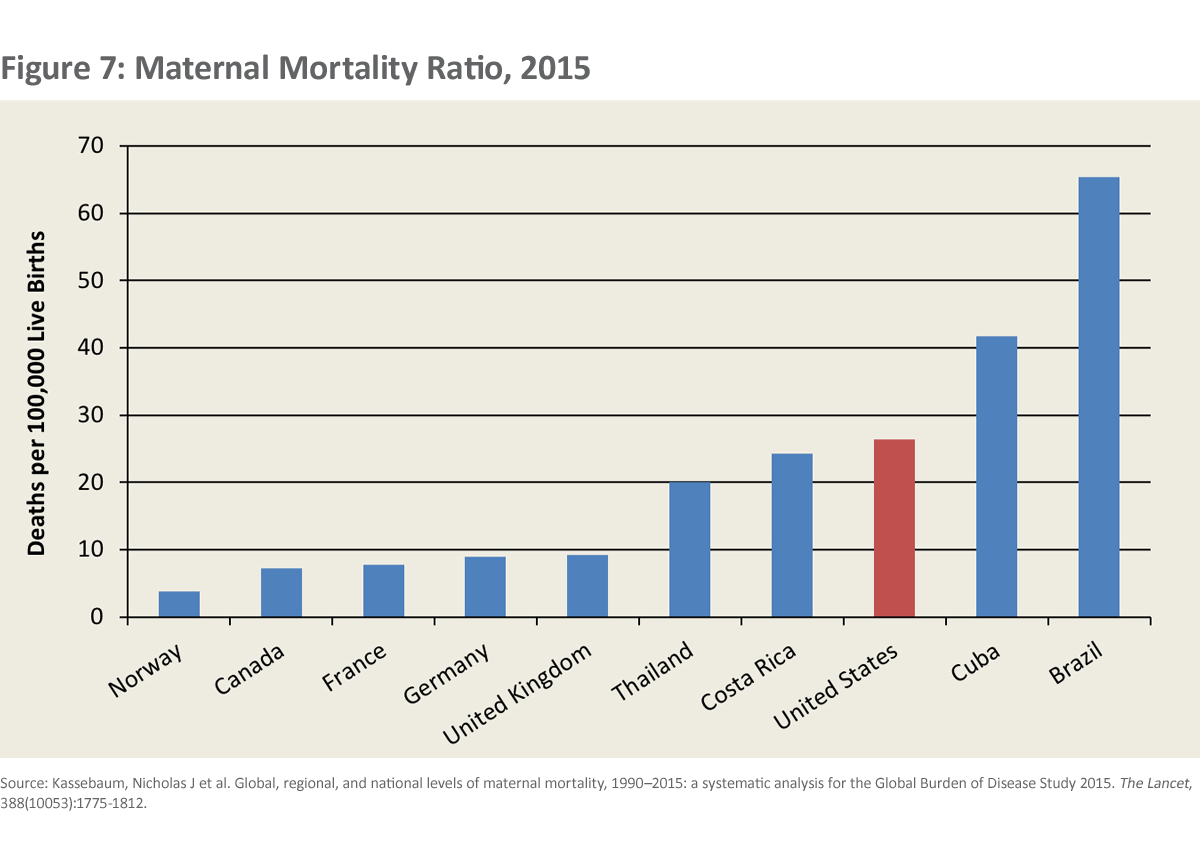

When we look at the maternal mortality ratio in the U.S. (Figure 7), it is hard not to hang one’s head in shame. The risk of dying of pregnancy-related causes in the U.S. is 3 to 7 times higher than in most high-income countries. The U.S. rate is about the same as the rate in New Mexico where I live now. The risk of dying a maternal death in New Mexico is about the same as that in Albania and China.

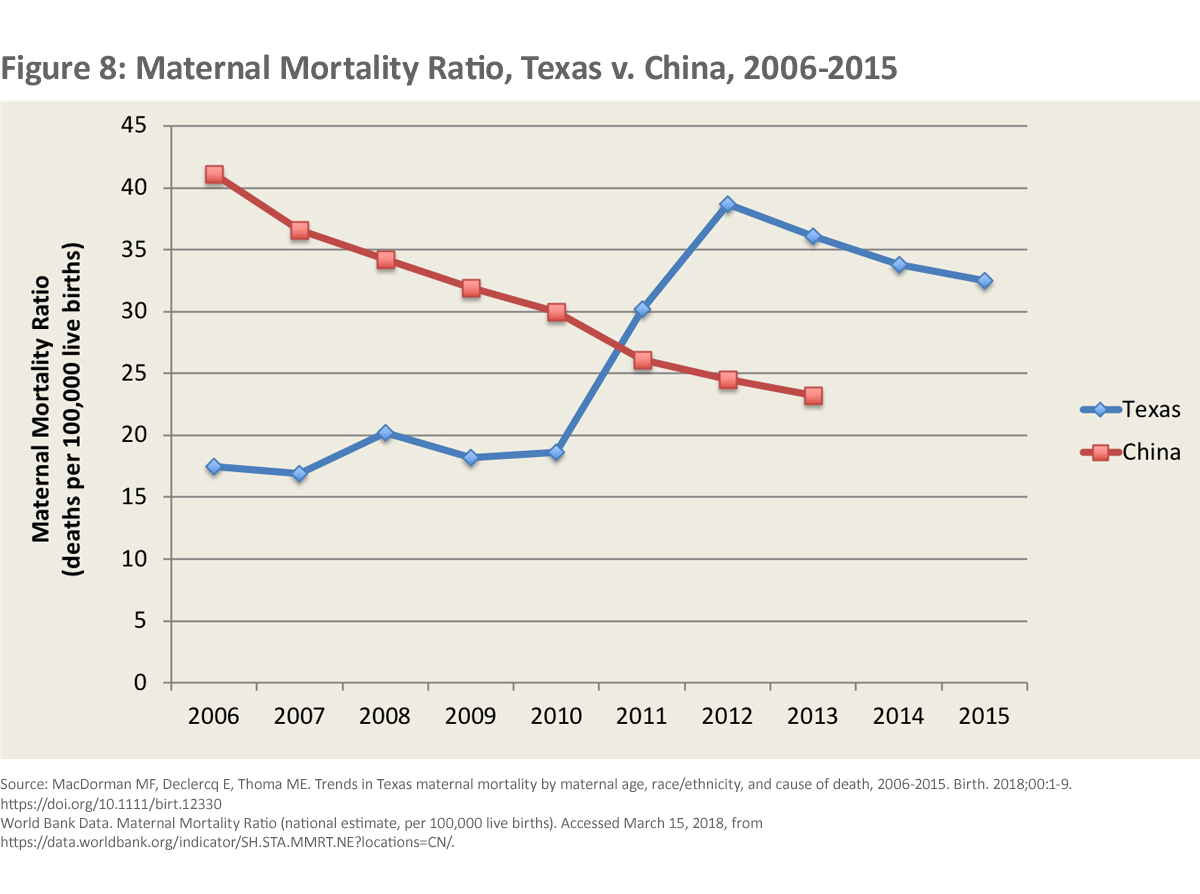

A woman now faces a 50% greater chance of dying of pregnancy related causes in Texas than in China (Figure 8). Moreover, women of color in the U.S. die maternal deaths at substantially greater rates than white women do.

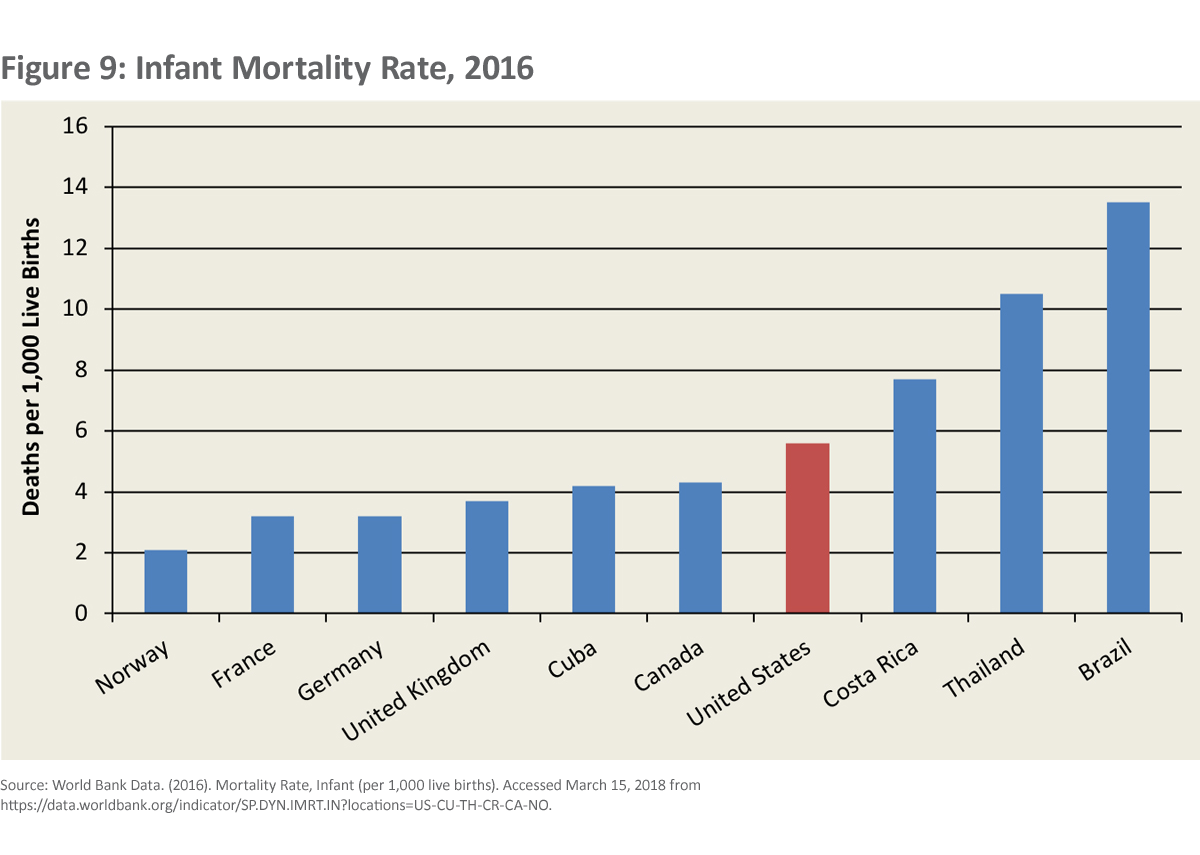

As we see in the Figure 9, our infant mortality rate is 3 times higher than in Norway, higher than that in other high-income comparators, and even higher than in some middle-income countries, such as Cuba.

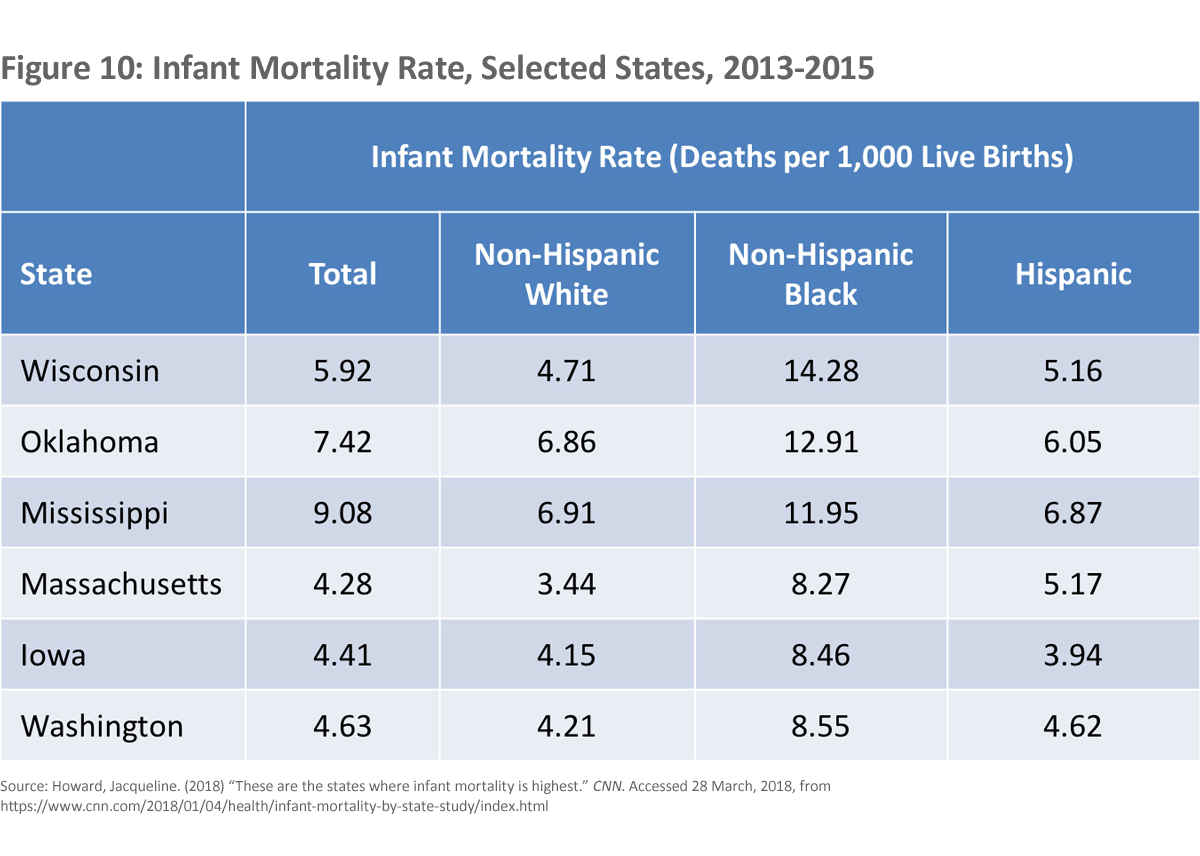

We also see that African Americans have an infant mortality rate that is more than twice that for white Americans (Figure 10) and about 6 times the rate in Norway.

As many of us are aware, the rates of obesity, diabetes, opioid use, and gun violence affect mortality in the US in a much more significant way than in almost any other high-income country.

Health Disparities

Finally, let’s look a little further at some markers of health and equity. I don’t need to tell you that in this category we are in a league of our own among the high-income countries and look very much like a lower- or middle-income country.

Enormous health disparities exist in the U.S. within states, between states, and across ethnic lines.

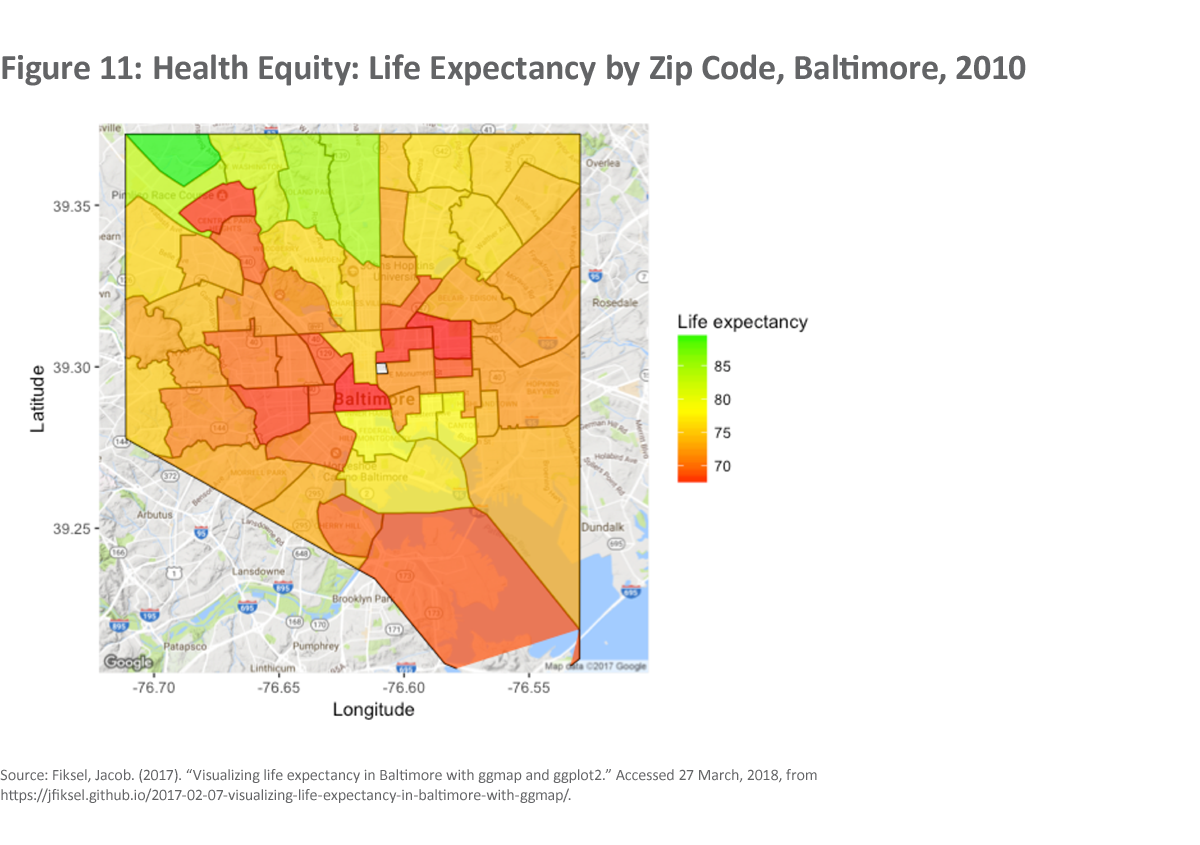

In Baltimore, for example, there is a 20-year difference between the lowest and highest life expectancy by zip code (Figure 11).

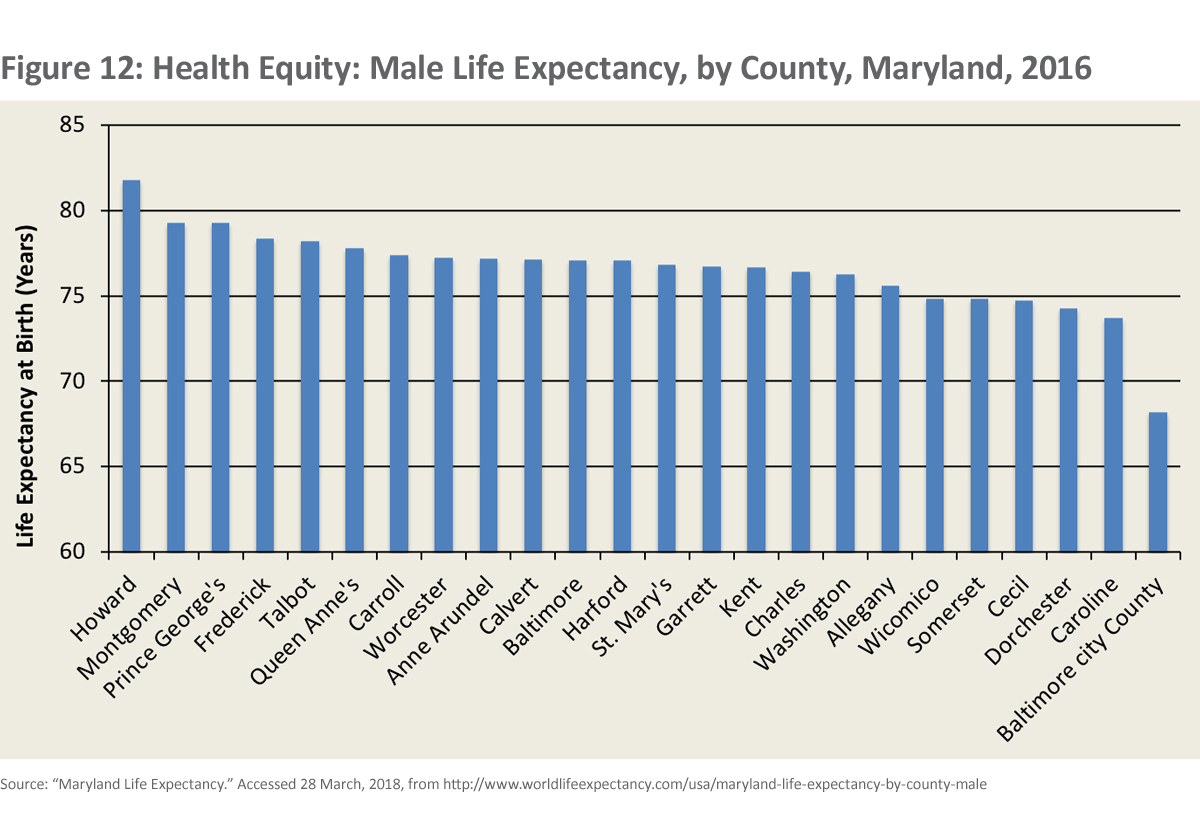

When we look at Maryland as a whole, and Maryland is a better off state, we see a 15-year difference for men and a 7-year difference for women between the lowest and highest life expectancy by county (Figure 12).

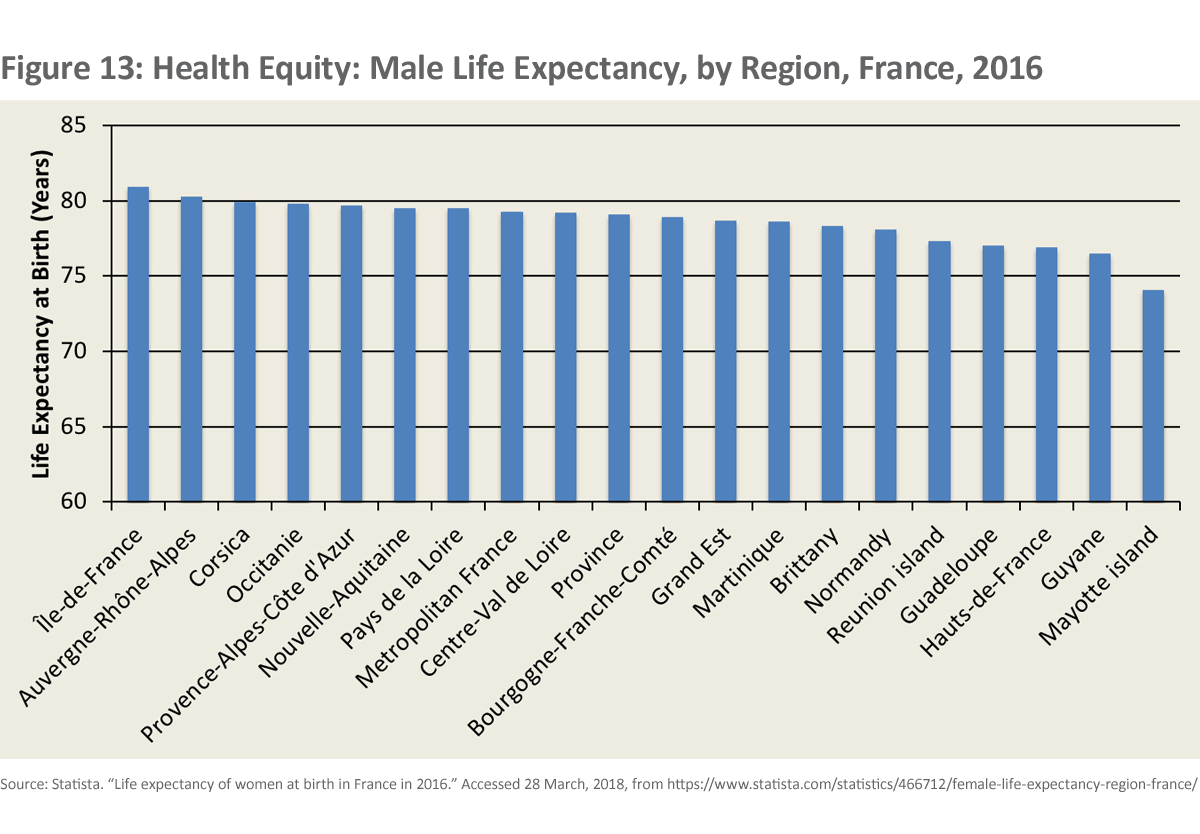

By contrast, when we look at France as an example of a large high-income country (Figure 13), the difference in life expectancy between the provinces, NOT including the overseas territories, is 5 years.

What to Do?

I want to suggest that a look at the U.S. in global perspective suggests a number of measures and approaches the U.S. might take to move us toward Universal Health Coverage (UHC) faster and at less cost. I am NOT naïve. I don’t believe for a minute that these will be done quickly. They are all completely wrapped up in the history, politics, and culture of the U.S.. However, even if it takes a long time, things, even in the U.S., can change.

So, let me give my list of a few critical measures that we need to take and that are suggested by the experience of other countries ...

Let’s stop discussing why we can’t insure all of our people and focus the debate instead on how to achieve UHC in fair ways, immediately, and at least cost. How is it possible that all other high-income countries, many middle-income countries and some low-income countries are ahead of us on this, some by decades and the Germans by more than 100 years?

Even low and middle-income countries from Rwanda to Ghana to Indonesia have committed to achieving Universal Health Coverage. These countries not only believe in health as a human right but also recognize that investing in the health of their people is cost-effective and will have long-term benefits on their economies and societies.

Here we can take our cue from Norway. When they reform their health system, they have the help of a national commission on fair priority setting in health. They set out criteria to maximize the health of their people, at least cost, with particular concern for the least well-off people and those who are sick. Let’s ensure that ethical and fair priority setting is in the curricula of all training related to health and health policy. Let’s resist the idea that 12 senators from one political party and of similar backgrounds can make health reform for a country as large and diverse as ours.

The US is spending more than it needs to – studies suggest that about 1/3 of all US healthcare spending is wasted. A new Harvard study says that the real driver of our high expenditure on health is high prices we pay for everything. Yet, most Americans have no idea what anything costs in health. By contrast, In Singapore all health care prices are listed by each provider like a dim sum menu. I think other evidence shows the Harvard study is only partly right but still highlights how much more we pay then we have to. What sensible country would prohibit negotiated prices for drugs, as we do in Part D? The Brits have made substantial use of an institute on cost-effectiveness. Australia only licenses drugs when they are more cost-effective than existing drugs.

Getting good value for health will also require changing the business model of healthcare. The incentives in the healthcare system currently promote procedures over consultation and frequency over quality.

No other high-income country appears willing to tolerate the disparities we tolerate. Disparities have many sources and are difficult to address. Many of them are social in origin. However, we need to try much harder to reduce them. Australia has a long way to go but their recent efforts to address the health of their indigenous people can be instructive. We need to see any significant gap between our basic health indicators and those of our comparators as inexcusable and unacceptable.

A book by Betsy Bradley called the American Healthcare Paradox suggests that other high-income countries achieve better health at lower cost by spending more and more wisely than we do on the social determinants of health, including maternity and paternity leave, child care, pre-school, etc..

Adult life expectancy is falling in the U.S., partly a result of the opioid crisis. The evidence from other countries suggests that we must start by addressing the crisis through a public health lens, rather than a criminal lens. We have more to learn from Portugal than from the present U.S. administration on this score. The same, of course, is true of the scourge of gun violence. We won’t learn much from Brazil or Honduras on this matter but we could learn much from the Swiss or the Aussies.

The Constraints to Change

Many of us understand what the constraints are to changing policies in the U.S.. A few that quickly come to mind would include:

- Privately financed elections

- Gerrymandering

- American “individualism”, social Darwinism, and antagonism to communitarianism

- American arrogance and ignorance

- A profit-oriented health system with key actors fighting for the spoils – at the expense of consumers

Next Steps

Despite the difficulties of moving in the above directions, let me suggest a few ways that we might try.

Perhaps one starting point might be to see changes led at the state level, at least where states have enough people to spread risk across insurance schemes and a commitment to UHC. Mass did, after all, set up a state version of UHC.

Another approach would be local efforts to address key gaps, such as maternal and infant mortality, opioids, and gun violence. These will hopefully, take account of best practices in both the US and globally. California seems to have done this well for maternal mortality.

A third, would be for the private sector to pioneer better approaches, as Warren Buffett and some others are trying to do now. Health costs hurt their competitiveness and they have a strong incentive to act. This won’t produce Universal Health Coverage but it might produce valuable lessons and incentives for the rest of the system.

We could also benefit from philanthropists who enable the development of a “movement” around the need for effective and efficient Universal Health Coverage and the filling of other gaps. At some stage Americans needs to understand that we don’t have the best health system in the world, that we lag other countries by years, and that we can and must do better. At some stage Americans need to understand that everything has a cost and the cost must always be paid. We can choose to make the system more effective and efficient or we can keep paying more than we need to do. Bloomberg is deeply involved in anti-tobacco efforts. Why not help enable Universal Health Coverage? Or efforts to reduce infant or maternal mortality, thereby also reducing inequity?

In the end, of course, everything is political and we need to vote for politicians who embrace UHC, have thoughtful and evidence-based ideas about how to achieve it and are sensitive to the large gaps in the US approach to health and our health status.

This blog is based on remarks given in March 2018 in Dayton, OH.

Richard Skolnik has worked for over 40 years in international development and global health. After 25 years at the World Bank, he spent 8 years teaching global health at The George Washington University. He recently retired from five years at Yale University, where he taught global health courses in Yale College, the Yale School of Public Health, and the Yale School of Management. Richard is the author of Global Health 101, Third Edition.